From ancient Greece to the modern workplace

The concept of mentoring has its origins in Homer’s Odyssey. In this Ancient Greek epic, Odysseus entrusts his young son Telemachus to the care of Mentor, his trusted companion, when he goes to fight in the Trojan War.

Three thousand years later, workplace mentoring typically involves an experienced leader providing guidance, advice and support to their mentee, who is seeking to develop their skills and advance their career.

This guidance can include a knowledge transfer, tips on how to handle difficult situations or helping the mentee navigate a company’s culture or politics.

Mentoring can also help foster a more diverse and inclusive workplace, as it provides opportunities for underrepresented groups to connect with and learn from experienced employees. In recent years, mentoring has also helped employees during the times of uncertainty, disruption, and change.

Effective mentoring programs drive talent retention

Effective mentoring programs have been shown to improve employee retention by helping mentees feel more engaged and valued. They also provide a sense of belonging, which according to McKinsey research is one of the most important drivers of retention.

In a separate study at Sun Microsystems in the US, involving 830 mentees and some 670 mentors, researchers measured the impact the company’s mentoring programs over a seven-year span. The results show a powerful correlation to engagement and retention (see visual below).

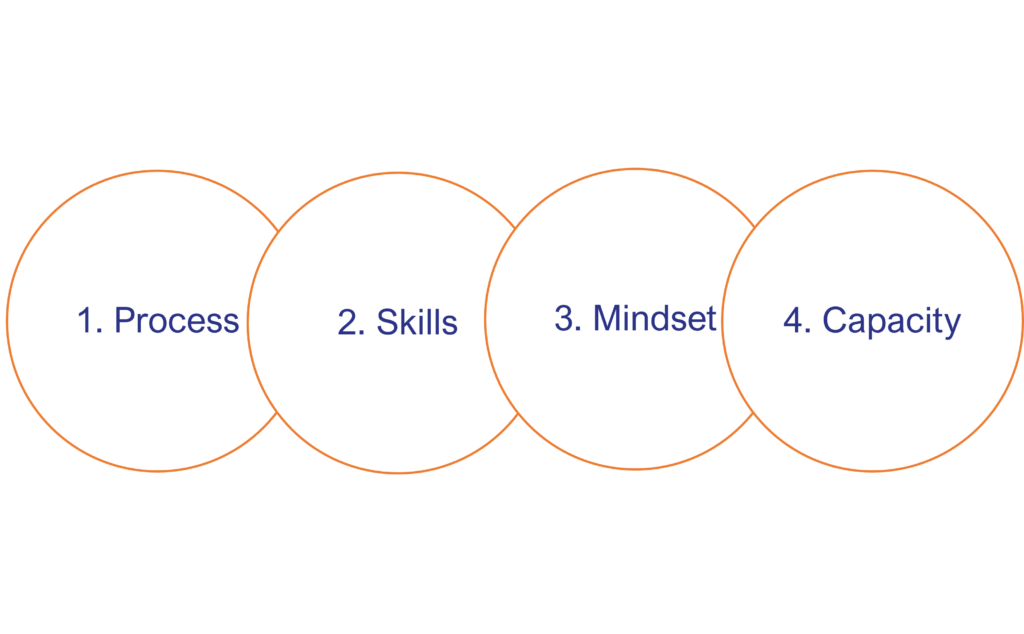

Why mentoring fails: The four “wheels” of successful mentoring programs

Given that effective mentoring programs drive engagement and talent retention, why do some of them fail to gain traction? In our own experience of supporting organisations to deploy successful mentoring programs, there are four distinct “wheels” that need to be operating together for forward movement. If one of these wheels is missing or not working, the mentoring relationship, or the program itself, can come off the rails (see image below)

- Process – Effective Mentoring follows a distinct process

The starting point of any mentoring relationship is the matching of mentor and mentee. The growth of mentoring programs in companies across the world has been accelerated in part by the adoption of platform technologies that makes it easier for the mentor/mentee matching process.

For many mentoring programs, that is where the process begins and ends.

However, the next important step in the mentoring process is the “chemistry check”.

Anyone who has ever followed an online dating process will know that being matched with a partner by a digital algorithm, doesn’t necessarily mean they are compatible.

Similarly, if the mentor and mentee don’t have chemistry, i.e., they are not compatible in terms of personality, communication style, intrinsic values or goals, the mentoring relationship may fail to get going.

Another step in the mentoring process that is often overlooked is “contracting”.

Contracting is establishing agreements about the foundations of a productive and effective mentoring relationship. These agreements—especially those around confidentiality—are essential for building the crucible of trust and psychological safety required for meaningful conversations. This is particularly true for internal mentor relationships where the mentee might want to be able to talk about delicate subjects—such as internal politics—without it being a “career-limiting” move.

- Skills – Being a mentor requires skill; so does being a mentee

Exceptional mentors consistently demonstrate a set of micro-skills including active listening, empathy, skilful questioning, and holding creative tension. These skills may seem like they should be second nature to knowledgeable leaders within an organisation. However, when we observe these leaders in actual mentoring conversations with their mentee, there is often a gap between what they know about these micro skills and what is actually showing up in real time in their one-on-one interaction. When we shine a light on these behavioural blind spots through observation process, we find the gaps can quickly close.

While skills development in mentoring programs is mostly focused on the mentor, often when mentoring relationships fail to progress, the problem is not a skills gap with the mentor, it’s a skills gap with the mentee.

When we sit down with mentors and mentees who are taking part in a workplace mentoring program, one of our questions is, “Who should be taking ownership of the mentor/mentee relationship?”

The misconception is often that it’s the mentor who takes ownership. In fact, it is the mentee who needs to take ownership.

Taking ownership as a mentee involves, for example, taking the initiative for scheduling meetings and setting clear objectives and goals for each meeting.

- Mindset – Start with the “Why?”

Mentoring relationships with a clear purpose breed success.

Some famous purpose-driven mentoring relationships include the poet laureate Maya Angelou as a mentor to Oprah Winfrey during her early career and Steve Jobs as a mentor to Mark Zukerberg when Facebook was a start-up.

Another famous mentoring relationship was Warren Buffett who was asked to be a mentor to Bill Gates in his early career. Both Buffett and Gates have admitted that their initial meeting was initially not of choice and that they were both reluctant to spend time with each other, wondering what they would have to talk about. But they quickly developed a strong connection and Buffett challenged Gates with questions that made him think about things differently regarding IBM and Microsoft.

Bill Gates stated that he had learned how to manage his time and prioritise people because of his meetings with Warren Buffett. Gates learned from Buffet how to be an analytical businessman. He has also credited Buffett with igniting a passion to deal with larger, world problems like poverty and disease. Bill Gates has used the same philosophies and transformed this mentorship into a global recognized partnership with his ventures.

- Capacity – Mentoring fails when there is no individual or organisational capacity

Mentoring meetings are “important” but they are rarely “urgent”. That means they are commonly squeezed out by last minute organisational priorities for the mentor. When mentoring meetings get cancelled continuously because of competing priorities, the foundations of trust in the mentoring relationship are shaken and the value of the mentoring diminishes.

The solution to this problem is building organisational “capacity” for the mentoring program by elevating its importance.

An effective mentoring program needs sponsorship from the executive and a communications plan to make sure the audience understands the value of the program, the benefits for them and how the program aligns to the organisational strategy.

To learn more about SMG’s approach to developing world class workplace mentoring programs, contact us here.