More than two decades of research, and our own experience of coaching leaders and executive teams, shows that it’s easy to lead when conditions are positive. However, strong leaders differentiate themselves when the organisation or the team are challenged. Over the past six years, there has been one leadership trait that has risen to the top in responding to these challenges – our resilience. Resilience is the capacity to manage pressure, to make complex decisions in uncertainty, and the ability to bounce back from inevitable setbacks.

In this article, we explore the practical nudges and micro-shifts to which we all have access in order to build this capability.

The neurology of performance under pressure

Being at our best

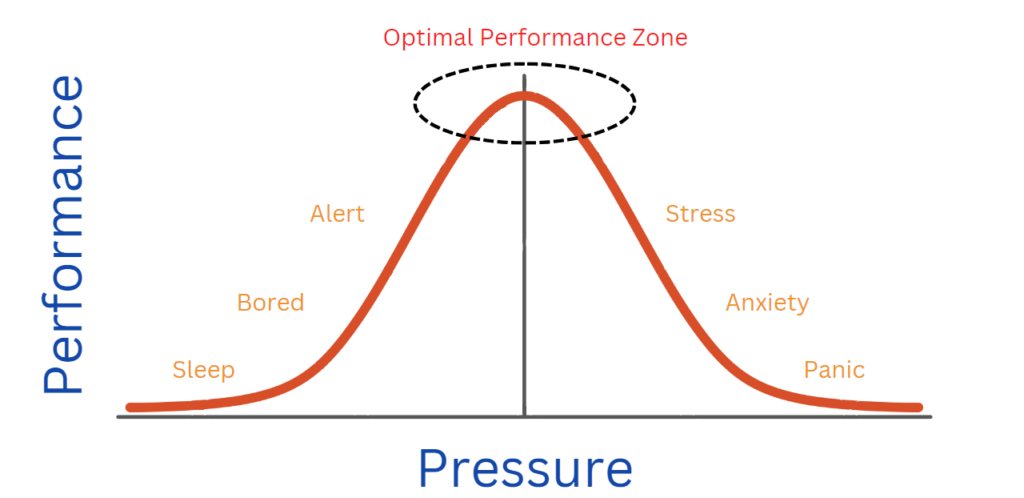

As the centrepiece of this discussion, let’s look at the ‘performance-pressure’ curve, one of the most validated correlations in social science. When we experience no stimulation or pressure, we feel safe, but we’re not operating at our full potential. When just the right amount of pressure is applied, we reach the ‘sweet spot of optimal performance’. If we were smart, we’d create work environments which accelerate us to this point and hold us here. However, that’s not typically the operating environment we’ve created for ourselves. So, when additional triggers and stressors are applied, a stress response is created.

Now if we’re tuned in, we’ll identify those triggers quickly and have a response to move back into our sweet spot. If we don’t, those triggers don’t go away, and they build, creating a deeper anxiety. If we don’t do the heavy lifting and get the right support, we’re at risk of panic and burnout. That may sound extreme. However as reported in HRD Magazine, the Microsoft Work Trend index published in 22 September 2022 showed that 62% of Australian workers reported being burned out at work, compared to the global average of 48% of employees. Furthermore, 66% of Australian managers suffer burnout compared to 53% of global managers.

With the World Health Organisation identifying burnout as a growing workplace syndrome, there is a risk this will become our new norm.

Our attitude to stress

Psychologist Kelly McGonigal’s insightful Ted Talk shows that our attitude to this stress response makes all the difference. When we view nerves positively as the mind and body giving us the stimulant we need to be at our best, our arteries open up, our blood flows and we have a healthy response to stress. However, if we view the same situation as negative, then the opposite occurs: our arteries constrict, our blood pressure rises and our adrenaline spikes. Our stress response is now unhealthy, rather than productive.

A tale of two systems – The prefrontal cortex and the limbic system

By understanding the fundamentals of how our brain operates, we can work with our brain’s resources, rather than against them. Core to this is understanding a battle going on between two parts of our brain. First is the prefrontal cortex (PFC), located in the frontal lobe. The PFC is responsible for all of our executive functioning: every time you need to learn something, remember something or solve a complex problem. Regardless of your role in your organisation, you operate in a ‘complex nonlinear system’, where there are multiple priorities and ways to break down the same problem. We all need our PFC resources to operate in this environment.

One potential barrier to this higher-order thinking comes from the limbic system, which is responsible for our emotional responses including our fight-or-flight response, or ‘amygdala hijack’. When activated, the limbic system gets really loud really quickly, absorbing all of our cognitive energy and leaving less resource for our poor PFC. In fact, studies show that about one-third of cognitive capacity is wiped out in an instant when the amygdala is activated, and so we quickly lose access to higher order cognitive functioning.

A common example we see in the workplace is the ‘angry e-mail’. When triggered and before thinking, we are belting the keys in response! Now if we’re lucky, we’ll avoid pressing ‘send’ and we’ll follow the age old advice to “sleep on it”. When we come back to that message it either gets completely reworded with the nuance it needs, or we send it straight into the trash. Now the limbic system is calm, the PFC is working well, and so we make better decisions. So if we are to be at our best while managing pressure, the toolkit here is focused on managing our limbic response and getting the most out of our PFC.

Your Toolkit for Managing Pressure

Part A is understanding how to manage the cognitive PFC side of performance.

The myth of multitasking

Science has shown that multitasking is not a human concept. Multitasking is a software engineering concept from the 1980s that describes when a device is working on multiple processes at the same time – concurrently, not sequentially. The human brain, regardless of intelligence, has not evolved to the point where this is possible. Rather than multitasking, what we are in fact doing is ‘switch tasking’, and research has shown three primary differences when we complete tasks in this mode:

- It takes a lot longer to produce the same output;

- The quality of work is reduced with a higher error rate; and

- There is an added level of stress and pressure.

We are designed to complete a task with laser-beam focus until completion, and then move onto the next task. When the human brain operates in this mode, it has formidable capacity. We have discovered genomes, put astronauts in space and put a super computer in the palm of your hand. However, again this is not the operating model we’ve typically created for ourselves. We’ll be on a Teams call, have our emails open, have a quick look at documents, as well as reading texts, and we are not doing any of these things at max capacity. Everything is taking longer, quality is reduced and you have baked in an incremental and unnecessary level of stress and pressure into your day.

Technique 1: Be deliberate

To harness your innate capacity for high-order thinking, think ahead to identify important high-value tasks that require your PFC at its’ best. It may be as short as a 15-minute task or a 30-minute conversation. Be deliberate about creating the right environment and removing distraction: shut off e-mail and your phone. You’ll complete that task faster, with a higher level of thinking and less stress or pressure. Furthermore, at the end of each day, identify the most important task to complete tomorrow and execute that task first before opening emails and other distractions. This habit creates critical moments of clarity and gives the PFC the clear air it needs for you to be at your best under pressure.

Building psychological safety

In Part B we move onto the limbic system, which is always looking for threats and rewards.

In the reward state, the brain releases comforting neurochemicals into the brain and body: dopamine, endorphins, oxytocin. We feel resilient, strong and confident. Our problem-solving is impressive, and our creativity and innovation is at its best. As leaders, we want to create this environment of positive chemicals for ourselves, and for our team. This is the science behind psychological safety – recently a popular term, but a concept that is 200,000 years old. As a species, we thrive better together with trusting relationships. The way we build our social connections creates and maintains psychological safety and promotes the release of the good neurochemicals.

Ask for help

Simon Sinek has shown that leaders who build trust the fastest are those most comfortable demonstrating a bit of vulnerability. Patrick Lencioni demonstrates that the first step to developing high-performance teams is vulnerability-based trust. This vulnerability is not necessarily sharing your deepest fears, rather saying “I don’t know” when you don’t know. This confident statement acknowledges the challenge you face, and that no one has all of the answers all of the time. This honesty releases good chemicals which build trust.

Asking for help and helping others is a multiplier. Not only are the helper and the helped experiencing positive chemical releases and a bonding relationship, observers are also experiencing a positive chemical reaction: a positive ripple effect has been created.

Technique 2: Ask for help

Think about what help you need to be effective and successful. Is it a bit of advice, some time, or some resources? Ask. We manage pressure better together.

By asking for advice, what we’re saying in this moment is, “I value you and I respect your judgement, intelligence and perspective”.

Technique 3: Help others

One of the easiest and most effective leadership tools we’ve come across is regularly asking three open questions: 1) How are you? 2) What do you need? and 3) How can I help? Even if specific help is not required in that moment, when asked authentically and regularly, postitive chemicals are shared, trust is built and our resilience enhanced.

Be grateful

25 years of positive psychology research has shown that individuals who remember to be grateful every day receive an immediate boost in their mental and physical health including resilience, stress tolerance, energy and focus. However, most of us forget to do this.

Technique 4: Say thank you

Think about someone who has helped you recently or who is contributing to you and the team by doing a good job. Reach out today and say thank you. By being specific, you add weight to your gratitude – i.e. “thank for helping with that specific task, this is the specific impact that this had”. To super-size this, communicate your thanks in a public forum like a team meeting. You’ll experience a flow of positive chemicals, so will the recipient and so will the team.

Just breathe

The final technique to managing our emotional resilience is the easiest and the most effective: remember to breathe. You breathe regularly every single day. However when under pressure we forget to do this properly and we starve our brain and body of the resources it needs to respond. Instead, we become tense and our breathing becomes shallow. Any high-performing field – whether in business, sport, performing arts, the military, and so on – all centre on breathing as the key to high performance.

Technique 5: Remember to breathe

Find your preferred rhythmic breathing technique whenever you feel under pressure from ’60 seconds of deep breathing’ to the ‘three breaths approach’ [one deep breath to leave the past, one deep breath to centre yourself in the present moment, and one deep breath to prepare yourself for your next task]. One highly effective breathing technique used in the Special Forces is box breathing: breathe in for four, hold for four, exhale for four, and hold for four, then repeat. A few cycles of this instantly changes your neurology and physiology. The science has shown that this is the fastest way to move from the right-side of the performance-pressure curve back to optimal.

Recently I had the privilege of speaking with a captain from the Australian Special Forces. He was describing his first mission as a captain which involved extracting an asset out of an Afghani village. While driving back to base, they inadvertently detonated an improvised explosive device (IED) and had come under attack. Out of the dust, he noticed that every member of his squad was looking directly at him, waiting for an order. He described how his training kicked in and everyone was extracted safely. I asked him what he did in that moment of extreme danger and pressure which allowed him to think and make the right decisions.

He just smiled at me and said, “I just remembered to breathe.”