How to Escape the Matrix of Workplace Conflict

The Matrix (Picture: Warner Bros.)

In a classic scene from the The Matrix, the main character Neo is offered the choice between a red pill and a blue pill by rebel leader Morpheus.

The red pill represents an uncertain future. It would free Neo from the enslaving control of the machine-generated dream world and allow him to escape into the real world. However, living the “truth of reality” is harsher and more difficult. On the other hand, the blue pill represents a beautiful prison that would lead him back to ignorance, living in confined comfort within the simulated reality of the Matrix.

This iconic movie moment serves as an interesting metaphor for how conflict arises in an organisation.

In any organisation there is a complex pattern of established relationships between the different functions. Like the Matrix, these patterns are invisible and play out in a consistent way.

For example, when a senior executive de-prioritises an initiative from a direct report, in their mind they are they are simply making a judgment call within the complex and competing priorities of their role. But when the direct report hears nothing about their prized initiative, it’s interpreted as an example of the executive’s “incompetence” or “indifference”.

Or consider a senior executive team that has developed an exciting new process for their teams. As the initiative is deployed, the excitement felt at the top doesn’t carry through to those in client-facing roles. Why? Because they are already overwhelmed with new systems and processes. Yet when they fail to implement the new initiatives, the senior executives consider them to be “inflexible”.

If those examples sound familiar that’s because these stories are replicated consistently across industries, geographies and cultures.

And that’s the point.

If we look at this using systems thinking, the process of understanding how things influence each other within a whole, these interpersonal dynamics are consistent because they are a result of the “system” or “context” in which we operate.

Like the character Neo, we are under the spell of a metaphorical blue pill and we can’t see that much of the angst and dysfunction that we experience in the workplace is created by the predictable dynamics of the organisational system.

And because we are blind to the system and its effects, we unconsciously take things personally when actions and outcomes play out in the matrix of relationships. When we don’t separate objective fact from interpretation, we tend to jump to conclusions – and those conclusions are about “fixing” the person rather than the system dysfunction.

Separating fact from fiction

In the 80’s there was a famous advert in the UK for the Guardian Newspaper called Points of View that makes the distinction between fact and fiction brilliantly well, and reveals our tendency to jump to conclusions.

In the opening sequence we see a skinhead running on a street towards our viewpoint. He appears to be running away from some men in a car.

Then we see the same scene from another angle. We see that the skinhead is not running away from a car, but towards a man carrying a briefcase. The skinhead appears to grab the briefcase. It looks like he is mugging the man.

Then we see the same scene from an entirely different viewpoint in which we can clearly see that the skinhead is running towards the man with a briefcase to save him from a huge pile of bricks landing on top of him.

The narrator ends with the slogan, “It’s only when you get the whole picture, you fully understand what is going on.”

It’s easy to jump to conclusions in the absence of the big picture, or the full context of a situation, because we are interpreting only the information that’s in front of us. We tend to tell ourselves stories about what is happening and why. When we see a skinhead running towards a man in business attire, the story we tell ourselves is, “he must be a mugger.”

In the absence of the full context, when we haven’t heard from the executive in weeks on our exciting new initiative, the story we tell ourselves is “they are incompetent” or “they don’t care about me”. Or, when the client-facing roles resist executing on the new process the story that the executive team tell themselves is, “they are inflexible”.

Escaping the Matrix down the Ladder of Inference

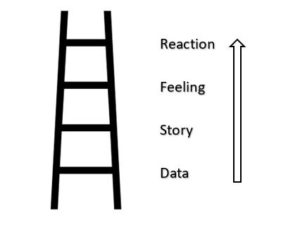

To escape the matrix’s power to create dysfunctional relationships, we simply need to take the “red pill” and make it visible. One way of taking this metaphorical red pill is to climb down The Ladder of Inference.

This conceptual framework describes the unconscious thinking process that we go through to get from data to a decision or action. The thinking stages can be seen as rungs on a ladder shown in the figure below:

The Ladder of Inference – Adapted from a model by Chris Argyris

We’ll illustrate the steps of this mental ladder using the example we’ve just explored of the man running down the street:

Data: This is the objective reality or irrefutable facts (e.g. a man is running down the street).

Story:We then begin the largely unconscious process of “storytelling” involving the following steps:

- We experience this data selectively based on our beliefs and prior experience (e.g. we focus on the skinhead’s appearance).

- We interpret what it means (e.g. “He is a nasty piece of work”).

- We apply our existing assumptions (“He’s about to do something nasty”).

- We draw conclusions based on the interpreted facts and our assumptions (“He’s going to mug that man”).

- We develop beliefs based on these conclusions (“All skinheads are nasty pieces of work.”)

Feeling:Based on the story we are telling ourselves we have an emotional response (e.g. self-righteousness)

Reaction:We then take actions that seem “right” because they are based on what we believe.

Getting beyond the Matrix by getting beyond the story

Typically, we follow these process steps of the Ladder of Inference without even realising it. Just as the first step of escaping the Matrix for Neo was about making it visible, for us it is about making ”visible”’ the subconscious stories we are telling ourselves.

The second step is to step back and look at the big picture of the situation and challenge the narrative of the story that we tell ourselves.

For example, for the leader who is experiencing “radio-silence” from the executive on the brilliant new initiative it is having the presence of mind to look at the broader context and challenge the underlying assumptions that are leading to a feeling of resentment.

For the executive team which is experiencing collective angst at the client-facing teams who refuse to embrace the new process with open minds, it is to stand back and challenge each other to look at the broader context of the situation.

The problem is that when we are caught up in an emotional response that is the product of an incomplete story, having the presence of mind to stand back and look at the system is not easy.

It’s like taking a red pill that takes us out of the comfortable prison of our familiar patterns of conflict and dysfunction.

And that’s a hard pill to swallow.

About the Author:

Mehul Joshi, Partner is a former award-winning BBC journalist and is now a sought-after consultant and executive coach in leadership development and employee engagement, with career spanning three decades and four continents.